There are countless problems in the world. They can be found in Sudan, Syria, England, Brazil and Ethiopia, to name but a few. Everywhere there are terrifying acts of nature and unnatural acts of terror. They are here, in America, too: gender and racial inequality, a lack of common-sense gun laws, incurable disease (and the profiting from it), the demonization of poverty, a culture of violence, the celebration of ignorance, and a demagogue wearing hate as a brand who wants nothing more than his bully in the pulpit. The lists go on and on, all of them, and it can seem overwhelming. Some issues affect us personally in our respective daily lives, others anger us from a never-ending newsfeed, and together they build one upon the other, brick upon brick of everything wrong, mortared by our shared fears, adhesive as they are.

They keep me awake at night.

Speaking to kids about such things may seem daunting, and granted, the level of discussion should always depend upon several factors that will vary from child to child: age, maturity, want of knowledge, and other things that parents know best, but the talk(s) should happen, nonetheless.

Why?

For starters, why not?

Of course there are arguments against it, namely the wonder and innocence of childhood being compromised by concerns they can do nothing about. I get it. I have used this same argument for years. I champion the concept of wonder and innocence as a life philosophy that should be curated for as long as possible — forever if you can get it; however, I do not believe innocence and information need be mutually exclusive.

What I do believe, is that allowing a child insight into the worst of us may very well inspire the best in them. Providing children access, albeit with parental guidance, to the ills of the world, puts perspective to our predestined privilege, even preventing said privilege from manifesting itself too fully. Instead, children that have a greater and broader appreciation of the workings of the world become more invested in it, more susceptible to empathy and compassion, more willing to stand for what is right. Show a child a problem, and chances are they may see a solution.

That isn’t to say that I would expect (or ask) future generations to fix all we have broke. Rather, I think they will be better prepared to avoid additions to it. I think it clear that our children are better than us, and their generation already has the capacity to address the issues, to tear down the walls we are building from so much fear and rote.

Children need to be able to defend themselves and what they know as good and right. We can give them the means for protection with context and knowledge. Don’t (only) tell them why you are against something, but show them what that something is against. Don’t guilt them into overindulging on a side dish because children are starving, well, everywhere, but show them what hunger looks like. Show them the effects of bad decisions and greed, the favela, the refugee, the farmer and the broken unions of people.

There is no better teacher than failure, and with that we have taught our children well. We may be overwhelmed by all of the problems in the world, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t also solutions, and by including our children in the conversation we are investing in them and their ability. After all, they are the future, and the future starts now. The wonder is theirs for the keeping.

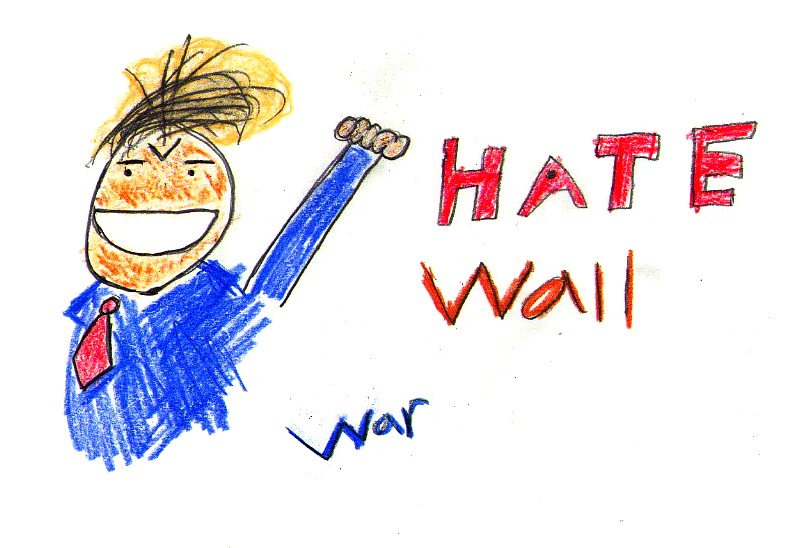

Child’s Insight into Trump Word drawing by Z. Honea.

Leave a Reply